Great products and services depend on their users having great experiences. But it’s not about what users do or how they do it, but rather why. Why they do what they do, why they keep coming back and why they tell their friends. Social Design explains the why behind these great experiences.

I’ll tell you a quick story. I had never heard of the Strand Book Store in NYC until earlier this year when I was walking around with a friend and she pointed it out to me. She apparently goes all the time and told me I’d like it. And I did. I even bought a new book from an author I like.

With technology today, we can get answers to anything factual right away. I could have looked up on my phone for bookstores in New York just as I could have looked up how to get to the store and if they carry books by this author. But the value of social is when I don’t even know I’m looking for anything at all.

In these cases and when we are faced with more subjective questions such as, “Where’s a good Italian restaurant?” or “What movie should I see?” or “Where’s a great museum nearby?” we turn to a community of people to help us out. These decisions are emotional, and who better to understand than other people?

Communities can be very useful, almost like a buffer between us and the world. In the wild, they’re an evolutionary defense mechanism against danger: a larger group is more powerful than an individual and the individual can look to the group for social cues on what to do. For us as people, having a community is more of an emotional attachment: we define it by the close people we surround ourselves with—our friends and family. We know them, we like them, they know us and they like us. We share thoughts, feelings, experiences and we turn to them for love and support throughout our lives because we trust them.

And though we have all kinds of relationships in our lives—with coworkers, neighbors or brands, long-lasting or short-lived, formal or intimate—it’s with our strongest ties that our trust lies. And this is the foundation of why Social Design works—because of this trust.

So when my close friend in New York tells me about a place I should visit, I trust her opinion and that she knows me well. And when our experience matches recommendations we get—that is, when we actually enjoy ourselves and learn something new—we not only feel special and thankful for the experience, but we also feel prompted to talk about it and tell our friends about it as well. We do this because we’re expressing ourselves by sharing the things we like and we want our communities to hear.

Trust is built through these conversations and everyday, hundreds of millions of people are having these interactions on Facebook and other social platforms, sharing thoughts, feelings, places they’ve visited, articles they’ve read, movies they’ve watched, and on and on. Social Design aims to harness this conversation, enhance it and build more of these serendipitous and valuable social experiences for everyone.

The Three Elements of Social Design

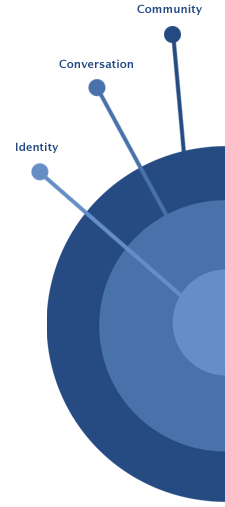

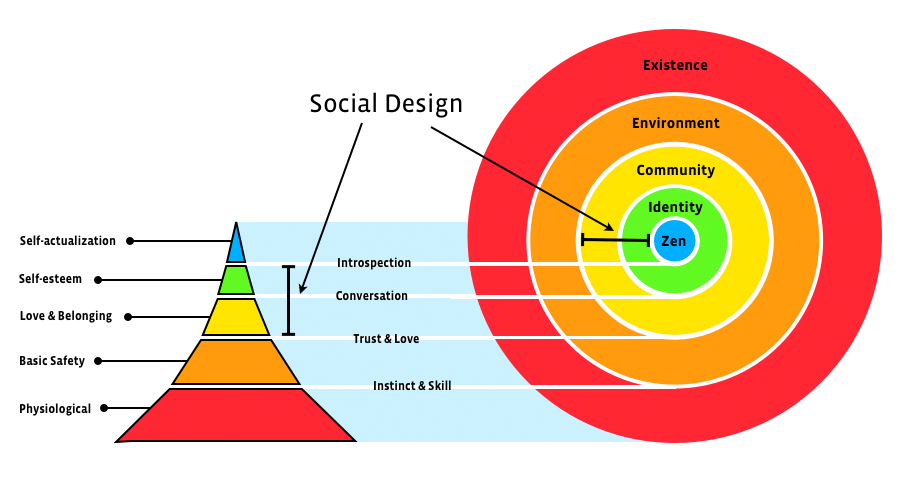

If we break Social Design down into tactical core elements, we see clearly how it’s comprised of three very distinct components: identity, conversation and community. Put another way: ourselves, other people and the conversations we have with them.

I like to diagram this using concentric circles, with identity in the center, conversation in the middle and community on the outside. The reason for this is because conversation really serves as the glue between identity and community. Conversation is how we express our identities to a community and how we receive feedback from it.

If we were to design a social product with this in mind, one idea might be to start from the center and work our way out. That is, allow people to create an identity, let them talk about it and build a community over time. This isn’t a bad idea at all – in fact, it’s how Facebook and a number of other social networks began.

When Facebook emerged in 2004, it was a simple site allowing college students to create and edit profiles of themselves. The editing was addictive; people kept logging in to see what had changed in friends’ profiles and to change things themselves. And, over time, this became a conversation—a timeline of life—and people built a strong identity and community of friends and family from it.

But now that this is in place – and used heavily by hundreds of millions of people everyday – it makes much more strategic (even practical) sense for social design to take the reverse approach and work from the outside in. That is, to utilize the existing community, define new kinds of conversation and let people continue to build their identities further.

A more iconic representation of the three elements of Social Design: Identity, Conversation and Community. Conversation is the glue between the identity and the community, binding the two together.

Utilizing Community

Facebook profiles have become people’s identities. They’ve spent countless hours curating them – adding friends, posting pictures, commenting on friends’ updates. This is their de facto representation of themselves, and they don’t want to recreate it from scratch every time they start a new product or service.

So rather than create an experience that starts with building a new identity, we should utilize what we can from what’s already on Facebook and build on top of it. Connect users to their friends when they sign up to a new service. Social apps aren’t social without other people and bringing a user’s friends automatically brings the established trust in a community. Use profile information to recommend content – people already know what they like and that’s why it’s on their profiles.

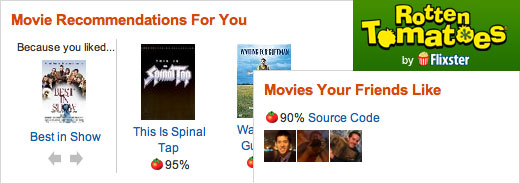

Rotten Tomatoes, for example, with the addition of Instant Personalization, shows users movies that their friends like as well as movies they might like based on the movies they already like, as listed in their profile.

Get the baseline in place so all that needs attention is the conversation – what they talk about and how they do so.

Building Conversation

Conversation builds trust. In fact, any real-time interactions associated with emotion build these strong bonds. It could be anything from sitting together and talking to dancing, protesting, jumping out of a plane, etc. Conversation is simply a generic term I’m using to describe the interactions between the self and the community and the stronger the associated emotion, the stronger the bond.

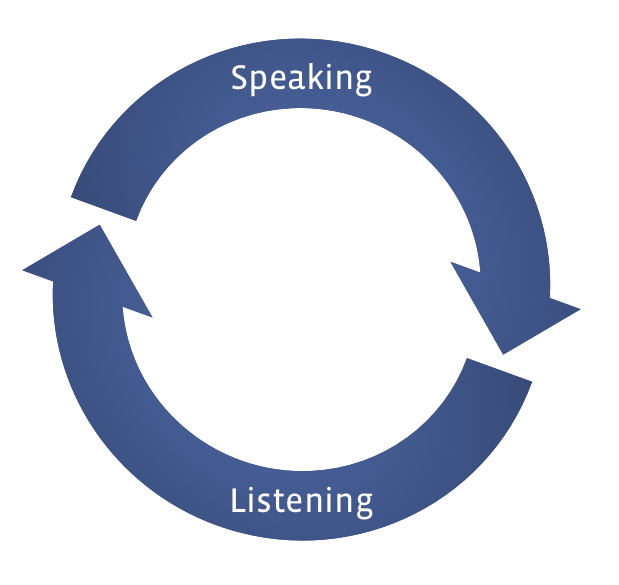

This is inherently a back-and-forth and therefore is comprised of two different experiences that play off each other. Generically, we can describe these as listening and speaking.

Listening

A listening experience is hypothetically if you were go to a restaurant you’ve never been to before and choose what to eat based on the recommendation of others. You’re essentially listening to the community’s thoughts and previous actions and using these to inform your decisions.

We already see this in many places online. People on Yelp, for example, can make comments on restaurants such as, “Try the hot chocolate.” And on YouTube, you can see ratings for each video that help you determine which ones to watch, since you probably don’t want to watch the bad ones. They say, “Watch this one; others liked it.” On many e-commerce sites such as Amazon, we see the same thing: reviews from people to help our decision-making.

But there’s a big problem here: we don’t always know these people. And they don’t know us. So how do they know what we like? How can we trust them to give a good rating? We can’t. There’s no established trust.

So what Facebook has done is remodel this same paradigm but scope it around your friends. Social plugins, for example, let people “like” things all over the Internet and then surface this activity to their friends. And because you see what your friends and trusted circle like, you’re more likely to care.

Again, because the value of “social” is when we don’t know what we want and we’re not really looking, showing activity spread throughout the experience constantly inundates us with potential conversation points and things of interest. We learn by watching others. It’s social encouragement and a form of mimicry if anything: if we see someone else we trust doing something, we’re likely to do the same.

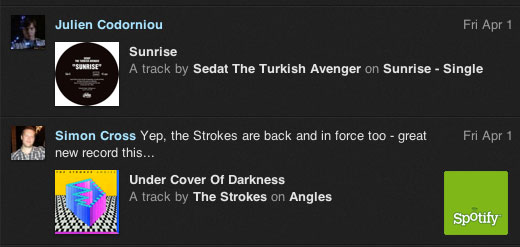

Spotify, for example, shows a feed of all the songs that users are sharing and adding to their playlists. It’s a personalized way for users to browse some of the latest and most popular songs.

When you connect with your Facebook account to Huffington Post, you see an activity feed of all the articles your friends have been reading lately.

Speaking

The other half of the conversation—and perhaps the most important part—is the speaking and the sharing. People have to engage in the first place, and will do so when they have the right motivation. The good news is that if people are sharing with people they trust, they are more likely to share more often and be open and honest.

Facebook has a number of ways for users to engage, including a number of options in the publisher (status, links, photos, etc.) and multiple ways to provide input and feedback (likes, comments, answers to questions, wall posts, etc.). And all of this activity is surfaced to users’ friends constantly through various distribution channels. We can’t help but listen.

The more contributions that are made to the system, the more activity exists to listen to and engage with. And likewise, the more activity there is to engage with, the more contributions can be made to the system. And this creates a positive feedback loop—a “virtuous cycle of sharing” as we call it—that grows exponentially. This is really the sweet spot: conversation fueling more conversation.

To summarize, a great social experience depends on conversation between the community and the self. And this is based tactically in three main elements:

1. Utilizing personal information and connections to build a personalized experience

2. Showing conversations, social context and activity everywhere

3. Making it really easy to talk, share, give feedback and engage

Curating Identity

The beauty of Social Design is that it plays to the most powerful form of motivation: the self, the identity. We share and interact with others because we want to, because we learn more about ourselves and because we feel better when we feel heard.

Social Design is actually central to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, I believe. After our physiological needs of food and water, and after our basic safety needs, we have a very interesting duality between needing love and belonging and our own sense of self-esteem. It stands to reason, given the diagram, that we base much of our own self-esteem in how the community sees us and how accepted we are. In other words, the community helps drive our identity. And it’s when we have that feeling of belonging and love that we can build our self-esteem and reach our full potential.

The experiences I mention already exist in the real world today; we’re not really trying to invent anything “new” here. But the Internet is becoming part of the real world and a reflection of it, a means by which we can communicate with one another more efficiently. With people at the center of the Web, more and more experiences that naturally happen in the real world are starting to happen online. With this in mind, as we design, we should take into account existing social truths, thinking carefully about the identities and respective communities we affect and building the best conversation tools for them.

Ultimately the value of social is bigger than anything material. It’s a way for us to close the gap between the self and the community, just as we’ve closed the gap between our other needs. We don’t have have to worry about food nor spend our lives hunting like other animals. Our ability to trust each other and work together as a species has built a safer environment in which to live. But individually, we do still worry about our futures, finding love, feeling heard, and knowing ourselves. Social Design starts us along this path.

For more information, check out the Facebook Social Design guidelines I wrote.

Like this article? You may also like these:

- One for All and All In One – How Simple Should Social Interfaces Really Be?

- Brand Devolution – A Logo Change Changes Our Trust